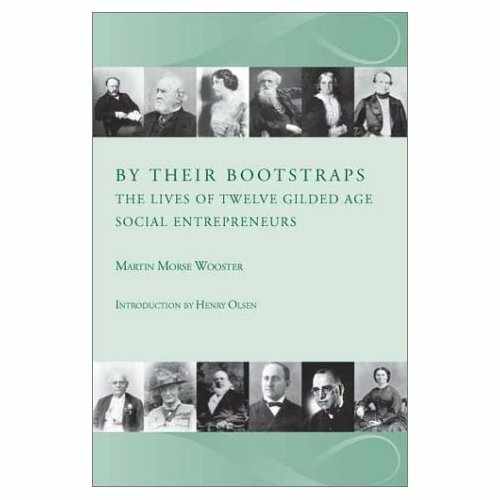

By Martin Morse Wooster

This book is sponsored by the Manhattan Institute’s Social Entrepreneurship Initiative. Our Initiative presents annual awards to some of the most notable social entrepreneurs in America today, people who are creating new non-profit organizations to tackle some of our society’s most pressing problems. Given this focus on action in the present day, one might ask why we would sponsor a book depicting the lives of people who lived over a century ago. The answer is that we see today’s resurgence in social entrepreneurship as a renewal of the spirit that flourished in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a spirit that saw the foundations of today’s independent, non-profit sector built by individuals who saw it as their responsibility to act to ameliorate society’s problems on their own without significant government oversight or involvement.The sector these people helped create is taken for granted now, but was quite unique when they began. Organizations that existed solely to provide benefits for others without charge were rare in the early 19th century, and even rarer in earlier times. Consequently, these people blazed their own trails in creating their groups; they had to be every bit as entrepreneurial in the setting of goals and the creativity of achieving them as any founder of a business. What distinguished them and the sector they were creating was the object of this entrepreneurial fervor: not the accumulation of wealth or the production of goods, but the betterment of their fellow men.

Given how successful they were, one might think their examples would have guided their successors and encouraged these second- and third-generation non-profit activists to achieve new heights. Unfortunately, this did not happen. In the 20th Century, talented, socially aware people turned to government as the outlet for their energy, building an extensive social welfare network that provided most of the money and direction for societal improvement. Much of this activity was funneled through the organizations built by the 19th Century social entrepreneurs, co-opting them and subtly limiting the very independent spirit that characterized them in their nascence.

What changed? Why did the socially aware entrepreneurs of the 20th Century differ so much in outlook from their predecessors? The answer lies in the intellectual revolution wrought by the Progressive movement in the early 20th Century, a revolution that changed the way Americans looked at nearly every aspect of their community life.

Progressives looked at the circumstances around them—rapid industrialization and growth of large corporations, rapid urbanization and concentration of poor people in cities, an explosion of scientific knowledge and approaches—and created an ideology to explain and guide these trends. They argued that decision making, whether in government or in particular firms, had to be centralized. They argued that only experts trained in a particular field could effectively guide the actions of a society or firm. And they believed that the effect of these two principles would create a rationally ordered, efficiently operating society which benefited all people.

These ideas took root and sprouted the forest of government agencies and specialized fields of expertise that we now see in all aspects of American life. Companies created intricate command-and-control hierarchies, headed by businessmen who often possessed Masters of Business Administration. Philanthropists created large foundations with professional staff to give away the money they had earned. And government mimicked both sectors, building their own large agencies staffed with career civil servants trained by the specialty schools of social work, civic planning, and others that sprung up to create the new class of experts.

These ideas dominated for many decades, and are still influential today. But the last two decades has seen a second transformation in the circumstances of life that has the potential to change American life every bit as much as the transformations that took place in the early 20th Century.

We have seen an explosion in decentralized decision making in private firms, as people have come to realize that individual spark and drive create wealth more effectively than a hierarchical, top-down system. This has fed an explosion in private sector entrepreneurialism, perhaps the largest explosion since the one experienced in the late 19th Century. People today believe they can solve problems on their own rather than join an organization that will take care of them and provide their direction, and they are changing American life with their beliefs.

Much like the change in attitudes in the Progressive era, these beliefs are spreading their influence into the worlds of government and philanthropy. Al Gore spoke of “reinventing government”, and politicians in both parties say they are moving toward devolving decision making in government, and giving average people more choices in how they receive and use their government benefits. Philanthropists are taking a more hands-on approach, seeking out new ways to give their money through “venture philanthropy” and other non-traditional methods. And some of the budding entrepreneurship in the air is finding its expression in socially useful ways; the MBA is finding that another dot-com or small business is not as rewarding as building a new school, or a new credit union that teaches immigrants how to save and invest for their futures.

The Social Entrepreneurship Initiative exists to spur this transformation on. Our awards highlight the work of successful social entrepreneurs with the hopes that more people will want to emulate them, and more philanthropists will seek them out and provide crucial “venture capital.” Our book places a focus on the philosophy that animates today’s movement, a philosophy that says social problems are best ameliorated when creative, talented individuals take on the challenge of solving them. We hope that people will come to see that private initiative can be harnessed to solve social problems, much as it was in the period of the entrepreneurs featured in this book. We anticipate changes in philanthropy, from attempts to create government programs to serve classes of recipients to an emphasis on funding innovative ideas and people who are judged and rewarded based upon measurable results. It is in this spirit that we publish this work, a testament to the ideas of an old generation and of the new generation yet to come.

—Henry Olsen

New York, New York

Read the full story at the Manhattan Institute’s website

Start Slide Show with PicLens LiteTags: , By their bootstraps: the lives of twelve gilded age soc, Henry Olsen, Manhattan Institute's Social Entrepreneurship initiativ, MArtin Morse Wooster

Rss

Rss